Tags

alliances, allies, Article V, Cato Institute, defense spending, Europe, free-riding, globalism, NATO, North Atlantic treaty Organization, nuclear war, Our So-Called Foreign Policy, Pew Research Center, tripwire, Trump

Whenever I’ve written about America’s security alliances lately, I’ve emphasized the unacceptable dangers they pose to the nation’s safety because they commit the United States to risk nuclear attack to defend countries that clearly now don’t belong on the list of U.S. vital interests – that is, countries so important to America that their independence literally is worth the complete destruction of major individual cities and even genuine armageddon.

Earlier this week, however, a reminder has appeared about another crucial reason to ditch the granddaddy of these alliances – the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Revealingly, it also strongly bears out President Trump’s charges that U.S. allies in the region where they’re concentrated (Europe) have been shamelessly free-riding on the United States. Indeed, the new information also underscores how the allied defense deadbeats are not only ripping America off economically (which seems to be Mr. Trump’s main concern), but how their cheapskate defense budgets are fueling the nuclear risk faced by the United States.

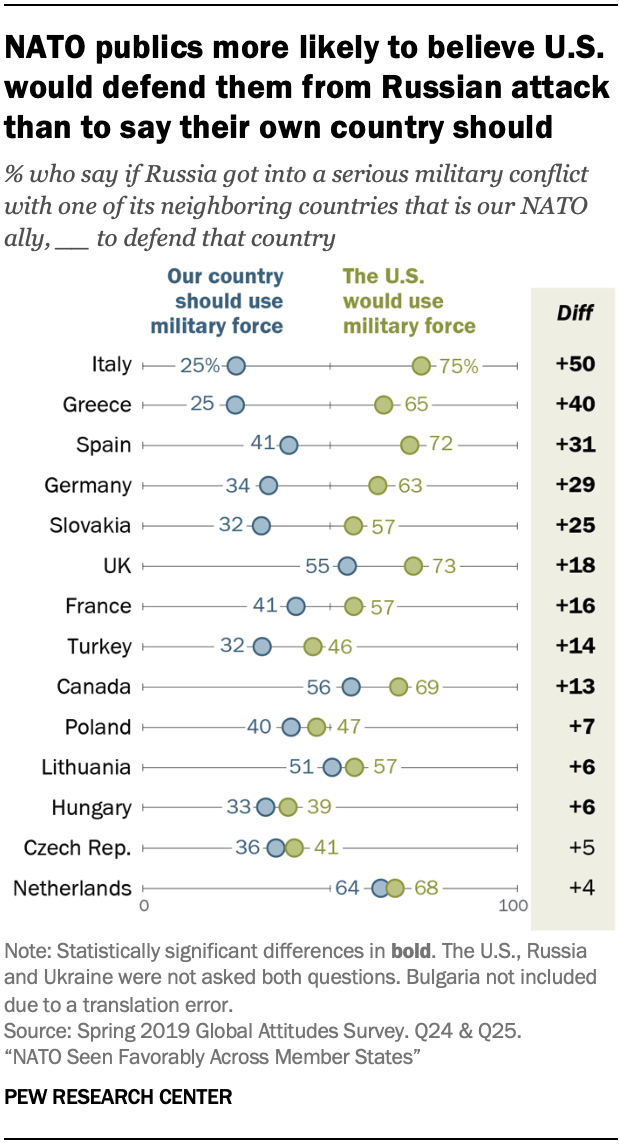

The evidence comes in the form of a new survey of the populations of NATO member countries (including the United States) released by the Pew Research Center, and if you stopped with the headline (“NATO Seen Favorably Across Member States”) you’d understandably think that everything is just dandy in alliance-land. But check out the chart below, which for some reason doesn’t appear until the middle of the Pew report. Its central message should outrage the entire nation.

For it shows that although NATO populations are confident that the United States “would defend them from Russian attack,” they’re decidedly unenthusiastic about their own countries participating in the defense of another NATO member. Specifically, a median of 60 percent of residents of NATO Europe (along with Canada) countries express such confidence in America’s military (including nuclear) guarantee (versus 29 percent who are not so convinced). But by a 50-38 percent margin, they oppose their own country joining in.

Of the fourteen NATO members surveyed, populations in only four (the United Kingdom, Canada, Lithuania, and the Netherlands) favored using military force to defend a fellow NATO ally. Yet in only four (Turkey, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic) did majorities not expect the United States would use force to defend them.

The gap was widest in Italy (where only 25 percent favored helping defend another ally versus 75 percent believing that the United States would ride to its own rescue) and narrowest in the Netherlands (where the numbers were 64 percent and 68 percent respectively). The Italians also were the most confident in the United States in absolute terms, and tied with the Greeks for the least willing to help out. The only NATO members in which majorities supported both propositions were the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Lithuania.

Americans should be infuriated by these results for several intertwined reasons. First, the obligation to come to the defense of a fellow NATO member is at the heart of the alliance (and indeed of any alliance) and is spelled out in Article V of the NATO treaty. Although it’s true that members can always ignore legal obligations when push comes to shove, that’s long been much more difficult for the United States – because of its policy of stationing its own forces in many NATO countries (as well as in South Korea) to serve as “tripwires.” The idea has been that once they’re bloodied by attackers, and indeed about to be overwhelmed (because of their relatively small size) American Presidents will have no real choice but to respond with the U.S.’ equalizer – nuclear weapons.

This prospect was supposed to deter attack in the first place, and the (very) good news is that this strategy worked to keep the peace in Europe throughout the Cold War, and is still working. The bad news is that during the Cold War, the main European beneficiaries were countries whose independence was arguably vital to America – like the United Kingdom, (West) Germany, and France. Nowadays, the main beneficiaries are countries whose independence was never even during the Cold War viewed as vital to the United States – principally, the former Soviet bloc countries.

Yet although the stakes have shrunken dramatically, Washington continues to brandish the nuclear sword. And this risky American strategy remains in place – as it always has – because the European allies’ military forces have remained far too small and weak to repel a Soviet/Russian attack on their own, or with the help of modest U.S. non-nuclear forces. Worse, the Pew results also strongly suggest that if war did break out, American leaders could not for long even count on the help of allied forces even if it was provided initially. That’s an unparalleled recipe for disaster on the actual battlefield.

The Pew findings make the reason for this alarming situation glaringly obvious – the allies have skimped on their military spending out of confidence that the Americans would always answer their call. So why shouldn’t they save the big bucks that would be needed for genuine self-defense and use them for other purposes – like generous welfare states? Even better, the Americans would be left holding the nuclear risk bag, since once any conflict on the conflict escalated to that level, the nuclear conflict would be fought over their heads.

In addition, the Pew survey reinforces the results of a poll released last fall and alertly reported by my good friend Ted Galen Carpenter of the Cato Institute (who’s also just come out with an important new book on the subject).

Let’s be totally clear: This European approach has always made perfect sense from a European standpoint. But it not only makes no sense for the United States – it’s a strategy that creates the danger of national suicide because of decisions that still yoke the country’s fate to manifestly unreliable foreign publics.

Weirder yet: Avowedly America First champion President Trump has been steadily increasing the U.S. military presence in NATO’s most vulnerable – eastern European – members without having secured military spending increases from the other NATO countries that are remotely game changing.

It’s tough, therefore, to avoid the conclusion that America’s NATO allies are now giving Washington the broadest possible hint that it’s time for the United States to leave – because they’ve become utterly unreliable on top of their defense free-riding. Why is the President acting as reluctant as any globalist to take it?

Hi again! Thanks for the welcome and your response. I was still a little unsettled about the exact content of the questions as actually asked in the surveys and wondered if there was some ambiguity or poor wording in them. But upon checking the precise language of the questions, particularly question 2 (i.e. number 25 in the Pew numbering), I’m afraid I must again disagree with your interpretation of them; that being said, it also seems that even the report authors themselves didn’t always interpret their own results quite correctly! After all, they’re the ones who chose the header for that chart, and that certainly wasn’t your fault.

Here’s the language of what they asked, according to their little section on methodology:

“Q24. If Russia got into a serious military conflict with one of its neighboring countries that is our NATO ally, do you think (survey country) should or should not use military force to defend _that country_?”

“Q25. And do you think the United States would or would not use military force to defend _that country_?” [I added the emphasis]

Therefore it becomes clear that, provided the respondents understood the question accurately – and one can never rule out the possibility that some proportion did not – the country being referred to as requiring defense cannot be the respondent’s own, but rather the one fighting Russia. This leaves open the possibility that while a given country’s public might not be willing to get behind an Article V military intervention on behalf of another NATO member fighting Russia, they might (I say again, might) be more prepared to pull their own weight when it comes to defending themselves as opposed to expecting us to cover for everybody.

I think that in general, the data in the report, while useful, could have helpfully been expanded upon in some ways. For example, let’s say there had been a follow-up question for those who said they were against supporting a NATO ally militarily, asking about their reasons for their stance, in an at least general way. Germans, for example, might answer to a large degree that they’re against war in general, not necessarily because they just don’t like their allies in NATO. Or perhaps Greeks are against military intervention in this context because they suspect the country they would be asked to rescue from Russian attack would be Turkey, and they might be marginally more supportive if the country being attacked were Bulgaria, for instance (I’m not as informed about Greek attitudes toward Bulgarians as I am about some of their other views). Thus, I see some room for nuance in the survey results which, alas, we can’t explore based on the data on hand.

(Tangentially, some other interesting food for thought in there – sometimes puzzling, at least to me, such as the finding that apparently almost 1 in 5 Americans are to some degree convinced that there exist parts of other countries that really belong to the US – what can they possibly have in mind? Baja? the Niagara Peninsula? Or the 23% of Britons who think the same – is there some segment of the British public that secretly wants to reconquer Ireland or something?)

Anyway, none of this really challenges your overall conclusion that the willingness of the publics of a great many of our NATO allies to honor their fundamental treaty obligations is very shaky and that this is a big potential source of trouble for us. It does make me wonder why we are really in NATO at all at this point. Certainly the question is worth asking.

Belated thanks again, Philip, but I really do think you’re over-thinking the content of the Pew questions. But I certainly agree with your point about how Pew could’ve helpfully gone into more detail. In fact, the superficiality and false choices that tend to dominate polls on foreign policy, trade policy, and immigration policy is a theme I’ve written on consistently here.

Hello! I just discovered your blog today. Has no one else commented on this article yet? It makes me wonder if I can’t see others’ comments for some reason.

That chart of European attitude distributions is very telling, yes. I think you misunderstood the second question a bit, though, assuming that the survey did indeed ask it in the way that you mention – it seemed to be asking respondents’ views on whether the US would go to defend the other unspecified ally that would be fighting Russia, rather than whether the US would defend the country being asked the question. The header on the chart is therefore also a bit misleading.

The high rate of majority yes-answers to question 2 and the spread between the first and second questions are therefore not as scandalous as they might seem to be. I still think the answers to question 2 are interesting, but for a somewhat different reason. I see that in general, the further away the queried constituency is from Russia, the belief that the US would defend whichever NATO member that was fighting Russia increases. Hungarians apparently having the lowest confidence in this reflects, I suppose, their having been directly invaded by Russia/the USSR once in living memory and our having done little about it in the direct sense, for various reasons. Czechia similar, for the same reason.

Interesting that Lithuanians seem to have more confidence, though, in our stepping in. It would have been interesting to see Romania’s responses as well, and those of the other Baltic nations to see if their attitudes would break the pattern or hold to it.

Belated thannks for the detailed comments, Philip, and welcome to RealityChek! Here, however, is how Pew put these matters to the NATO publics – and the conclusions drawn: “When asked if their country should defend a fellow NATO ally against a potential attack from Russia, a median of 50% across 16 NATO member states say their country should not defend an ally, compared with 38% who say their country should defend an ally against a Russian attack.

“Publics are more convinced that the U.S. would use military force to defend a NATO ally from Russia. A median of 60% say the U.S. would defend an ally against Russia, while just 29% say the U.S. would not do so. And in most NATO member countries surveyed, publics are more likely to say the U.S. would defend a NATO ally from a Russian attack than say their own country should do the same.”

So it’s clear that my conclusion is on target: “[A]lthough NATO populations are confident that the United States ‘would defend them from Russian attack,’ they’re decidedly unenthusiastic about their own countries participating in the defense of another NATO member.” That’s not to say that some share of NATO publics don’t both favor militarily aiding another ally and are confident in the US defense guarantee. But clearly a large share opposes such military aid of a fellow treaty ally and remain confident that the US will fulfill its own defense guarantee to them. For an alliance based on the principle that an attack on any one shold be regarded as an attack on all, that’s pretty disturbing. And since the US shoulders the greatest military burden in NATO ranks, yet faces the least geopolitical risk, allying with many countries that don’t look very reliable looks like a formula for (needless) disaster on the battlefield, not to mention running an equally needless but far more dangerous risk of nuclear attack.