Tags

Advanced Technology Products, ATP, China, exports, goods trade, imports, Made in Washington trade deficit, manufacturing, non-oil goods, services trade, Trade, trade deficit, trade surplus, {What's Left of) Our Economy

Today’s official U.S. trade report, which covered both the month of December and the entirety of 2023, was full of excellent news for the U.S. economy. Especially noteworthy was the huge (18.76 percent) drop in the annual deficit last year – the biggest such fall-off since the gap nearly halved during the Great Recession year 2009 – even though 2023 economic growth was strong. Moreover, the 2023 level of $773.43 billion was the lowest since the $652.88 billion of CCP Virus year 2020.

Nor did that excellent trade news stop there by any means. The closely watched, still huge goods trade shortfalls with China, in manufacturing, and in advanced technology all showed major improvement, too. So did a less closely watched but crucial indicator – the non-oil goods deficit, which reveals the trade gap resulting largely from free trade deals and other U.S. trade policy decisions.

The major drop in the overall deficit stemmed in part from a new record in goods and services exports – which climbed 1.16 percent from the previous all-time high of $3.018 trillion to $3.053 trillion. And part resulted from a 3,60 percent decline in overall imports, from 2022’s record $3.970 trillion to 3.827 trillion.

The goods deficit fell from 2022’s record $1.183 trillion to $1.062 trillion – also the lowest level since 2020. And the services surplus jumped by 21.32 percent, from $232.82 billion to $288.24 billion. That figure was the second best ever (after 2018’s $300.16 billion) but the increase was the greatest since 2011’s 28.08 percent.

One cautionary note should be made, however. All of the above improvements followed long stretches of worsening trade balances. So it remains far from clear whether the nation’s trade picture has entered a genuinely better phase.

Turning to the narrower trade balances, the longstanding and still enormous goods deficit with China last year tumbled to its lowest level ($279.42 billion) since 2010 ($273.04 billion), early during the recovery from the Great Recession. Further, the 26.91 percent nosedive was the biggest on record in an official data series going back to 1985.

U.S. Goods exports to China decreased by 4.03 percent in 2023, to $147.81 billion from $154.01 billion. The new total was the lowest since CCP Virus year 2020’s $124.81 billion. Goods imports from China sank by 20.34 percent, from $536.31 billion to $427.23 billion – a tumble that was the biggest ever.

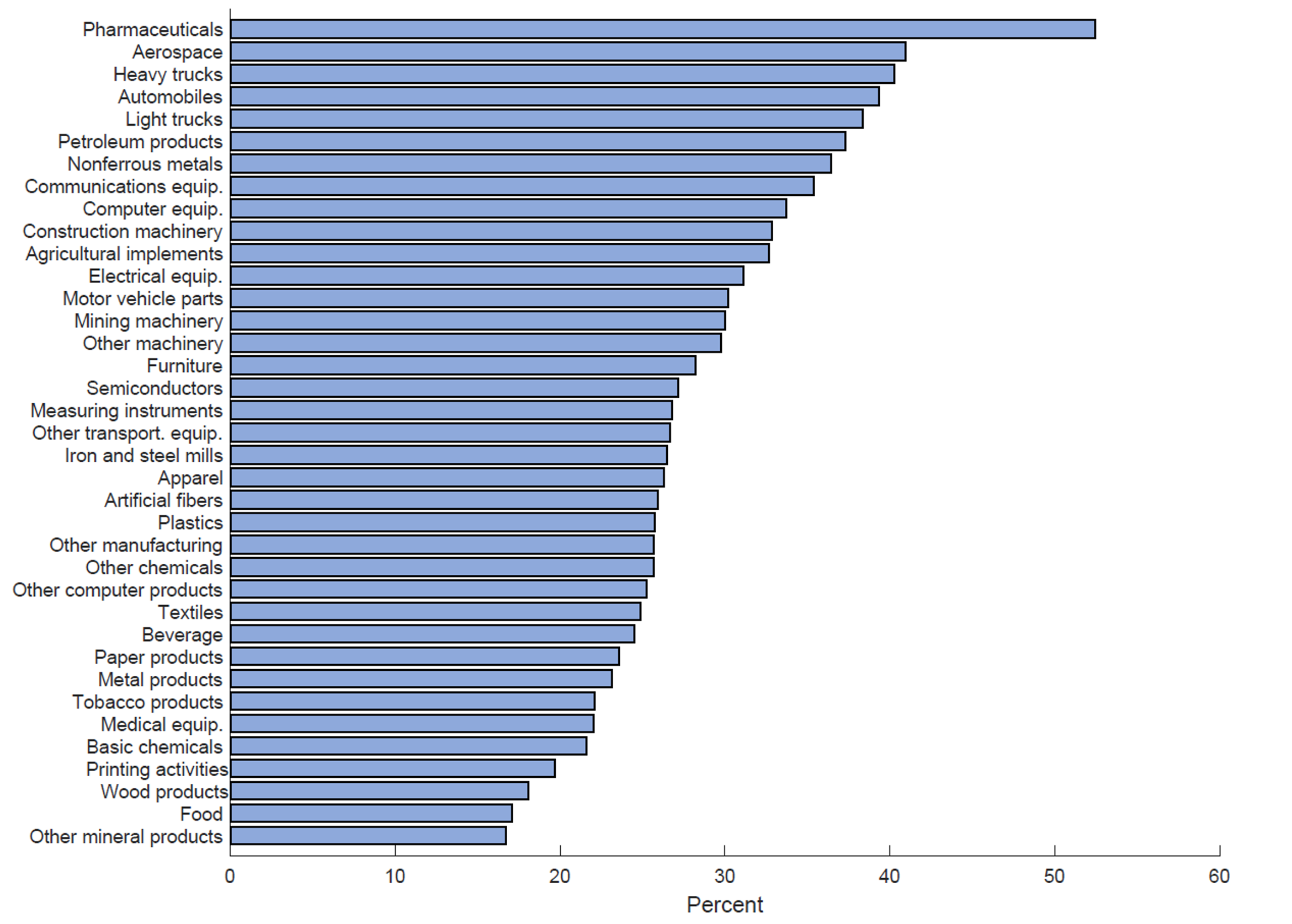

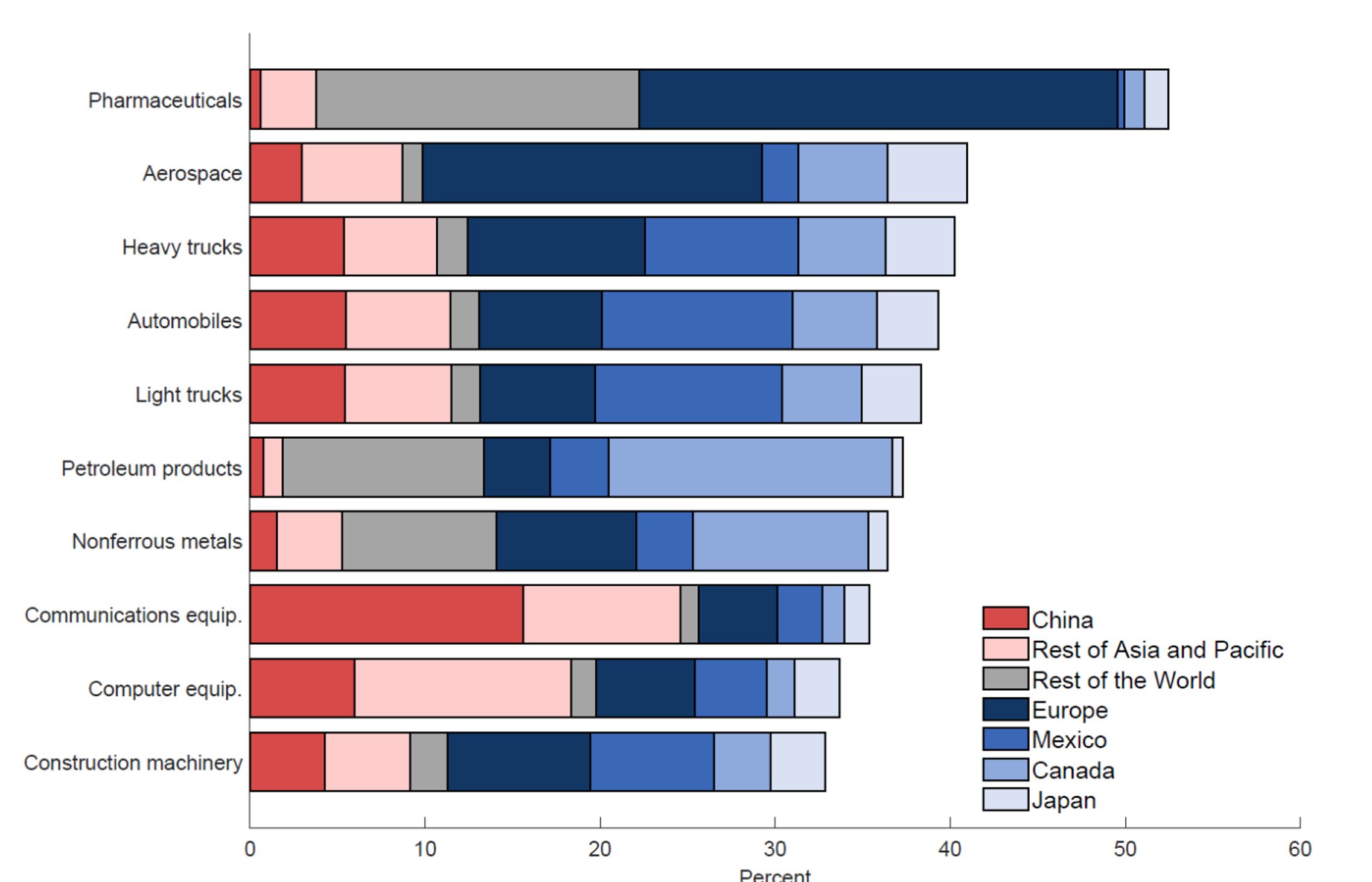

The manufacturing sector enjoyed a good trade year, too – at least relatively speaking. The chronically towering deficit shrank in absolute terms (from $1.500 trillion in 2022 to $1.386 trillion) for the first time since the Great Recession year 2008 (when it dropped from $611.67 billion to $578.00 billion.

Manufacturing exports slipped by 0.44 percent, from $1.294 trillion to $1.288 trillion. But manufacturing imports fell by much more – by 4.26 percent, from $$2.7931 trillion to $2.6740 trillion).

In Advanced Technology Products (ATP), the deficit in 2023 shrank for the first time since 2016. The improvement of 9.79 percent (from $242.70 billion to $218.93 billion) was the biggest since 2013’s 10.78 percent.

ATP exports increased 6.94 percent from a record $391.05 billion to a new all-time high of $418.22 billion. Imports also hit a second straight new record ($637.15 billion) but inched up just 0.53 percent, from $633.79 billion.

Also dropping year-on-year was the trade gap in non-oil goods – which can be considered the “Made in Washington trade deficit” because of its close connection with U.S. trade policy. Last year, the shortfall narrowed for the first time since 2017, declining by 8.26 percent, from $$1.193 trillion to $1.095 trillion.

Non-oil goods exports fell in 2023 for the first time since 2020 (from $1.758 trillion to $1.746 trillion) but this 0.67 percent decrease was dwarfed by the 3.74 percent drop in non-oil imports, from $2.951 trillion to $2.841 trillion. This decrease was also the first since 2020.

On a monthly basis, the total trade deficit in December climbed by 0.51 percent, from $61.88 billion to $62.20 billion. One curiosity here, though – the November shortfall was revised down by a large 2.09 percent, from $63.21 billion.

The goods deficit worsened by 0.78 percent, from $88.39 billion to $89.08 billion. And the services surplus rose by 1.40 percent to a new record $26.87 billion. This total broke the old mark of $26.51 billion, set in January, 2018.

Combined goods and services exports advanced by 1.54 percent, from $254.33 billion to $258.25 billion. Goods exports alone were up 1.84 percent, from $168.14 billion to $171.23 billion, and their services counterparts reached their fifth consecutive all-time high, improving by 0.97 percent, from $86.13 billion to $87.02 billion.

Total imports rose, too, in December, by 1.34 percent, from $316.21 billion to $320.45 billion. Goods imports increased even more, by 1.55 percent, from $256.53 billion to $260.30 billion, and services imports worsened by just 0.78 percent, from $59.68 billion to $60.15 billion.

The goods trade gap with China widened by 2.28 percent on month in December, with the rise from $21.59 billion to $22.09 billion the first on a sequential basis since September.

U.S. goods exports to China slumped by 13.64 percent on month in December, from $13.90 billion to $12.01 billion. That total was the lowest since September’s $11.83 billion and the decrease the biggest since May’s 16.53 percent.

America’s goods imports from China dropped, too, but by just 3.95 percent, from $35.49 billion to $34.09 billion. Yet the December figure was the lowest since April’s $33.08 billion.

The December manufacturing deficit of $107.76 billion represented an 8.39 percent decrease from November’s $116.15 billion and the lowest monthly total since last February’s $100.05 billion.

Manufacturing exports in December improved by 1.99 percent, from $104.39 billion to $106.47 billion, while imports were off by 2.86 percent, from $220.53 billion to $214.22 billion.

Even better were the ATP trade figures. In December, the gap narrowed for the second straight month, from $21.25 billion to $17.95 billion. The fall-off of 15.52 percent was the biggest since November, 2022’s 19.87 percent, and the monthly total was the lowest since last June’s $17.22 billion.

ATP exports advanced by 2.71 percent, from $36.00 billion to $36.97 billion – the second highest total on record after September’s $37.11 billion. ATP imports, however, sagged from $57.24 billion to $54.92 billion. This 4.06 percent decrease brought the deficit to its lowest level since September’s $57.56 billion.

The non-oil deficit edged up by 1.44 percent in December, from 89.53 billion to $90.82 billion. These Made in Washington exports improved by 1.61 percent, from $141.71 billion to $145.01 billion, while imports were up by 1.48 percent, from $232.24 billion to $235.83 billion.